Court Reporter: I attend the courts and my reports are circulated in the newspapers of Oxford, Derby, Worcester and elsewhere. My pieces can be curtailed or extended depending on my readers’ taste for the sensational. Readers might remember that back in April 1825 Hannah Read had been arrested for the murder of her husband, James Read.

Judge: Mr Goulburn.

Mr. Goulburn: Your Honour, I would like to state the facts of this case. The deceased had been a soldier in the late wars, serving in Royal Wagon Train that made such a name for itself during the battle of Waterloo. At the time of his death he was in receipt of a small pension from the Chelsea Hospital. He had been married to the prisoner for between eight and nine years; but in consequence of mutual disagreements they had lived apart for two years before March last. The deceased, however, hearing that his wife had formed an adulterous connection with one Waterfield, by whom she had a child, insisted on her quitting that man, and again living with hm. To this she complied, but at the same time threatening that she would do for her husband. I am obliged to call the attention of the jury to this fact, because the proof of the crime alleged against the prisoner is wholly of a circumstantial nature. Therefore it is necessary in investigating this crime to take into consideration the whole of her conduct before and after the death of her husband.

Judge: Circumstantial?

Mr Goulburn: Yes, Your Honour. To this end I call my first witness, Thomas Read, the brother of the deceased.

Thomas Read: It was back on the sixth of March this year when my brother took his wife to live with him again. She had been living in Sheepshead with a man named Jonathan Waterfield and had had a child, which she did not blush to confess was his. On her return, though, Hannah behaved badly towards James, to the point were I confronted and remonstrated with her, threatening to have her brought here, Your Honour, for her misbehaviour.

Judge: You did, did you?

Thomas Read: On the Monday following, the twenty-first of April, she again left my brother, but I was able find her and bring her back to him. At twelve o’clock that day she sent for her husband to go with her to Foxton to visit her relatives there. It would be a journey of about seven miles. The last time I saw my brother was as he left Shearsby to go with his wife to that place. By six o’clock the same evening Hannah had returned and called for me. She told me that her husband had run away from her mad. When I asked her what she meant by that she said:

Hannah Read: “When we got below Gumley, Jem began to dance and jump about as if he were mad; then he damned and swore, and fell onto the grass, and tore it up with his hands. After that, he jumped up and ran as hard as he could towards Debdale-wharf. I went to the bridge but could only look after him.”

Thomas Read: “Why did you not alarm the people in the neighbourhood?”

Hannah Read: “I was too much frightened to do so.”

Thomas Read: “Hannah, I fear you have pushed my poor brother into the navigation, and have drowned him there.”

Hannah Read: “Good Lord, Master, we were never within a closes’s breadth of the navigation.”

Thomas Read: I then called upon the new constable in the village to keep her in custody while gathered people together to assist me in searching for my brother. The following morning, as I was engaged in dredging the canal, I pulled up my brother’s corpse from a bridge near Foxton. I said to Hannah, who was there with me at the time, that the body appeared to be bruised.

Hannah Read: “If there are any bruises, he made them himself, for he tumbled down along the towing path as if he were mad.”

Thomas Read: This seemed contrary to what she had told me on the previous evening. She told me afterwards that he had tumbled into the canal, about eighty yards from the bridge, and that she had held his hat out to try to save him.

Mr. Goulburn. Thank you, you may stand down. I now call upon James Alney, the constable at Sheepshead, to tell us what happened when the deceased went there to recover his wife.

James Alney: I went with a man from Shearsby to the house of one Jane Wright. Upon my knocking on the door and asking if Hannah Read and John Waterfield were in the house, Hannah put ther head out of the window and called back inside to Waterfield.

Hannah Read: “O Lord, John, here is Jem come back!”

James Alney: The man from Shearsby insisted on her going back with him.

Hannah Read: “If I do, I won’t live with you; I would sooner murder you.”

James Alney: Then she threw a wooden weaver’s bobbin, as big as my arm, at her husband in the street.

Mr. Goulburn: Mary Gamble.

Mary Gamble: Hannah came to me that Monday, before she and James set off for Foxton, telling me that her husband had insisted on her living with him, but that she was against this and had said:

Hannah Read: “Damn him, I’ll do for him.”

Elizabeth Whitmore: I was there when Mr. Read was endeavouring to persuade his wife to live quietly with him, heard her say:

Hannah Read: “Damn you, I’ll never live with you; I’ll finish you between this and Monday night.”

Ann Robinson: Hannah Read came to my house on the evening when her husband was drowned, and told me that he had run off mad towards Gumley. I told her “You will be guarded until your husband is found, dead or alive. People think you have drowned him; and if you have, you are sure to be hanged.” She said:

Hannah Read: “Nobody saw me drown him; and therefore no one can swear against against me”.

Mr. Goulburn: I call Robert Johnson, boatman.

Robert Johnson: I saw two people on that Monday afternoon near the bridge at Foxton. There was a man wearing a smock-frock, and a woman, who had a child in her arms, wore a red gown. The next day I was helping to drag the canal, and pulled out the body of the dead man. When found, his right hand was still in his breeches pocket. I believe the man we pulled out of the canal was the same as the one I had seen the previous evening.

Mr. Goulburn: Call back witness Read!

Thomas Read: When I saw them leave the village, they were dressed as Johnson described. And the place where Johnson saw them was in the opposite direction to where Hannah said they had been going.

Court Reporter: Another witness proved that that they were dressed in the manner described, and that they were seen near the lock. Then the Coroner Mr. Meredith Esq. was called:

Charles Meredith: I have here an examination of the prisoner..

The Judge: Which I will not hear read. I don’t agree with this practice of taking confessions from people in my gaols and producing them on their trial. Let people speak for themselves, I say. What can you tell about the body you were asked to look at?

Charles Meredith: The deceased met his end by drowning.

Court Reporter: The prisoner, who during the examination of the witnesses had frequently contradicted their statements and was now called upon for her defence. She roused herself from a sort of stupor into which she had fallen, and in a low voice and wild manner protested that she was wholly innocent of the charge made against her. She described her husband’s conduct to have been frantic, and inexplicable, and that he had left her suddenly and fallen into the river.

The Judge: Members of the Jury, you have heard the testimony of several witness against the prisoner, and yet all the evidence is merely circumstantial. I urge you to consider this evidence with the most scrupulous attention, giving the prisoner the benefit of your doubts, if any should arise, concerning her guilt.

Court Reporter: After deliberating a quarter of an hour, the jury pronounced a verdict of..

Foreman: Guilty.

Court Reporter: The learned judge’s placing the black cap upon his head aroused her again from stupor, but when he addressed her by name she responded by a frantic shriek of melancholy fear and horror. She continually interrupted him by such appeals as:

Hannah Read: Save me! Oh, save me! For God’s sake, do not hang me! Oh save me for the sake of my six children, and my baby of six months old!

The Judge: Execution to take place next Friday morning. Afterwards her body to be taken down and sent to the Infirmary for the benefit of the anatomists.

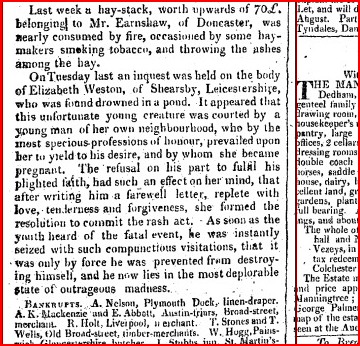

Image: Leicester Castle, 1821, looking towards the Criminal Court where Hannah Read was tried.

© 2017 Shearsby History Notes.